Illustration by Dr. Gheorghe Constantinescu.

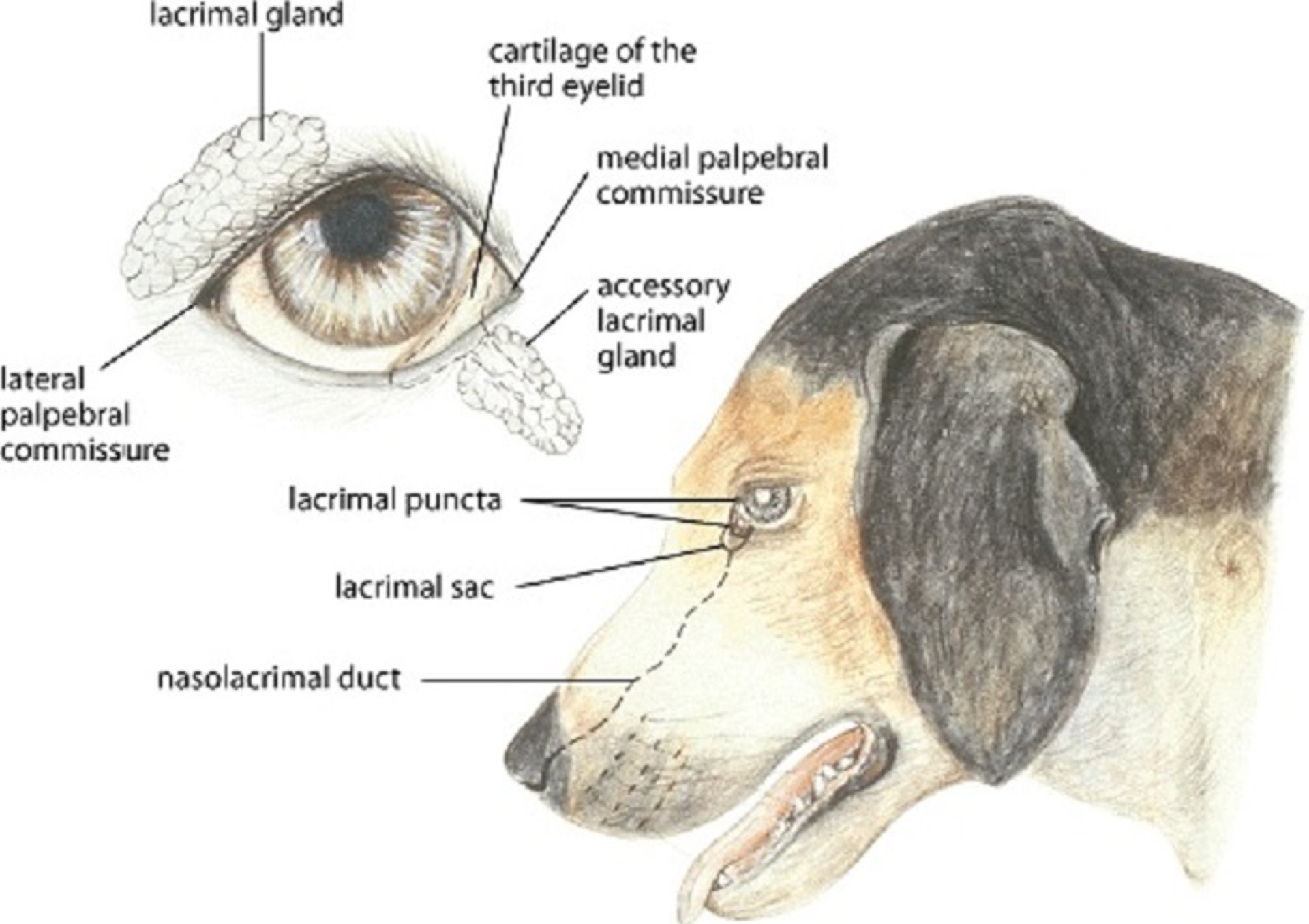

Tear production and drainage are vital for the health of the outer eye; these functions occur via the nasolacrimal system. Tear glands within the orbit (lacrimal and in some species Harder gland), as well as the superficial tear gland of the nictitating membrane (third eyelid), produce the aqueous portion of the preocular or precorneal tear film. This tear film consists of three layers: an outer lipid layer (from the meibomian glands), middle aqueous layer (from lacrimal and third eyelid glands), and deep layer (mucus) from the goblet cells within the conjunctiva. Most domestic species also have two nasolacrimal puncta near the medial canthus; an exception is the rabbit, which has only one punctum. These puncta lead to the two nasal canaliculi, which meet at a lacrimal sac (within the bony lacrimal fossa), and then to the nasolacrimal duct, which terminates at a nasal punctum.

Hypertrophy, inflammation, and prolapse of the gland of the nictitating membrane (cherry eye) is common in young dogs and certain breeds (eg, Beagle, Boston Terrier, Bulldog, Cocker Spaniel, Lhasa Apso, and Pekingese). Surgical replacement is recommended when the condition persists or recurs. In the acute stage, the red glandular mass swells and protrudes between the globe and the leading margin of the third eyelid. Although the swelling may recede for short periods, the gland often remains prolapsed. Because it is a major tear gland, it should be preserved. The gland should be replaced and anchored with sutures to the orbital rim, periorbital fascia, or nictitans cartilage, or covered with adjacent conjunctival mucosa (envelope or pocket techniques). Either suture or pocket techniques are recommended to allow for proper function of the gland and to decrease the incidence of keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS). Partial or complete excision should be avoided. Complete excision predisposes the patient to KCS (see below) in 30%–40% of dogs in later life. Surgical resolution of cherry eye still predisposes ~20% of these dogs to future KCS. Therefore, the tear production of these dogs should be monitored after surgery.

This young Boston Terrier with cherry eye shows bilateral inflammation and prolapse of the nictitating membrane.

Courtesy of K. Gelatt.

A thumb forceps is being used to expose the inflamed, prolapsed nictitating membrane (cherry eye) of a Boston Terrier's eye.

Courtesy of K. Gelatt.

A prolapse of the gland of the third eyelid in a dog immediately before (A) and after (B) surgical replacement of the prolapsed gland.

Courtesy of Dr. Ralph Hamor.

Courtesy of K. Gelatt.

Dacryocystitis (inflammation of the lacrimal sac) usually is caused by obstruction of the nasolacrimal sac and proximal nasolacrimal duct by inflammatory debris, foreign bodies, or masses pressing on the duct. In acute cases the medial lower eyelid may be swollen and painful. Inflammatory exudate may be flushed from the lower lacrimal punctum and/or distal nasal puncta. The condition can be confused with carnassial tooth infections in dogs. Dacryocystitis results in epiphora, secondary conjunctivitis refractory to treatment, and, in dogs, occasionally a draining fistula in or below the medial lower eyelid. This condition is also common in horses. Irrigation of the nasolacrimal duct reveals an obstruction of the duct, reflux of mucopurulent discharge from the lacrimal puncta, or both. Nasolacrimal flushing is required to re-establish patency of the duct; if flushing is not curative, contrast imaging may be necessary to establish the site, cause, and prognosis of chronic obstructions. In these cases, treatment consists of maintaining patency of the duct and instilling topical antimicrobial solutions and potentially systemic antimicrobials and anti-inflammatory agents. Tubing (polyethylene or silicone) or 2-0 monofilament nylon suture temporarily catheterized in the duct may be necessary to maintain patency during healing. When the nasolacrimal apparatus has been irreversibly damaged, a new drainage pathway can be constructed surgically (conjunctivorhinostomy or conjunctivoralostomy) to empty tears into the nasal cavity, sinus, or mouth.

Left image courtesy of K. Gelatt. Right image courtesy of Dr. Bret Moore.

Imperforate lacrimal puncta are an infrequent cause of epiphora in young dogs, but in foals and young camelids, atresia of the nasal (distal) end of the nasolacrimal duct is a common cause of early epiphora and chronic conjunctivitis. It is usually indicated by a compressible swelling on the floor of the nostril. In calves, multiple openings of the nasolacrimal duct may empty tears onto the lower eyelid and medial canthus, causing chronic dermatitis. Treatment in dogs, foals, and young camelids consists of surgically opening the blocked orifice and maintaining patency by catheterization for several weeks during healing.

Keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS) due to an aqueous tear film deficiency is termed "quantitative KCS" and is the most common form of KCS. Quantitative KCS is usually bilateral and idiopathic, and usually results in persistent conjunctivitis, mucopurulent discharge, superficial corneal vascularization, superficial corneal pigmentation, and fibrosis. Corneal ulceration may also occur. KCS occurs primarily in dogs and rarely in cats. In dogs, it is most often associated with an autoimmune dacryoadenitis and destruction of both the lacrimal and nictitans glands. Distemper, systemic sulfonamide, heredity, and trauma are less frequent causes of KCS in dogs. KCS occurs infrequently in cats and has been associated with chronic feline herpesvirus 1 (FHV-1) infections that scar the conjunctiva and openings of the tear ducts. In horses, KCS may follow head trauma, but it is extremely rare. A complete lack of tears causes acute onset of KCS and a very dry and painful cornea and conjunctiva. In chronic cases, conjunctival mucoid exudation is continuous and most evident in the morning.

Moderate, diffuse conjunctival hyperemia and mild, mucoid ocular discharge; typical of early KCS.

Courtesy of K. Gelatt.

Conjunctival mucopurulent exudates, dry and lusterless cornea, and keratoconjunctivitis; all characteristic of subacute KCS.

Courtesy of K. Gelatt.

A vascularized and pigmented cornea and thickened, inflamed conjunctiva with mucoid exudate are characteristic of chronic KCS.

Courtesy of K. Gelatt.

Topical treatment of quantitative KCS consists of the use of artificial tear solutions and ointments, and if there is no corneal ulceration, antimicrobial-corticosteroid combinations can also be considered. Lacrimogenics such as topical cyclosporin A (0.2%–2%, every 8–12 hours), tacrolimus (0.02%, every 8–12 hours), or pimecrolimus (1%, every 12 hours) often increase tear production. Of note, topical forms of tacrolimus and pimecrolimus for dermatological use should not be used in the eye. Cyclosporine increases tear formation in ~80% of dogs with Schirmer tear test (STT) values ≥ 2 mm wetting/minute. If there is no increase in STT value after 2–3 months of treatment with topical cyclosporine, a switch to an increased concentration of cyclosporine or to another tear stimulant, such as tacrolimus, should be considered. Dogs with neurogenic KCS generally have unilateral clinical signs, as well as a dry nostril on the ipsilateral side. Ophthalmic pilocarpine mixed in food may be useful for neurogenic KCS (dogs 20–30 lb [10–15 kg] should be started on 2–4 drops of 2% pilocarpine, every 12 hours). Mucolytic agents (eg, 10% acetylcysteine) lyse excess mucus and restore the spreading ability of other topical agents. In chronic KCS refractory to medical treatment, parotid duct transplantation is indicated. In general, canine KCS requires lifetime topical lacrimogenic treatment.

"Qualitative KCS" occurs when the lipid or mucus layer of the tear film is abnormal, resulting in an unstable tear film even if the aqueous portion of the film is within normal limits. A rapid tear film breakup time or positive staining of the conjunctival and corneal epithelium with a vital stain such as rose bengal or lissamine green is diagnostic for qualitative KCS. Qualitative KCS can be treated with lubricating gels and/or ointments that help to stabilize the tear film.